No. 351 at Middletown

Cadosia

NYO&W vestibule car No. 25

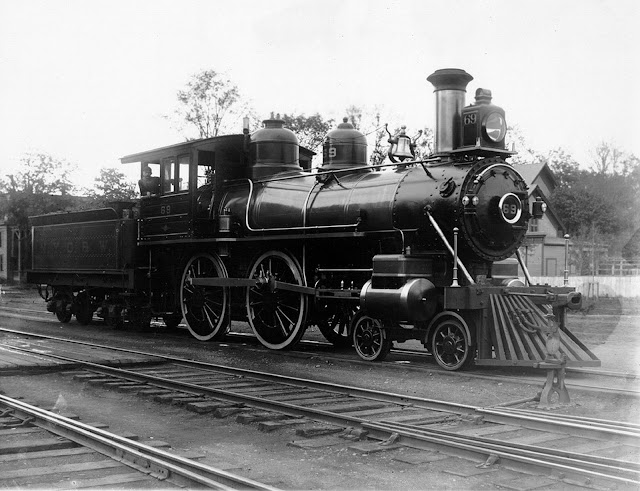

No. 53 at Norwich

No. 69

No. 95

No. 108 at Walton

No. 116

No. 227 at Cadosia

No. 105 at Middletown

No. 105

No. 457

No. 24 at Middletown

No. 82

No. 115

No. 134 on coal trestle at Cadosia

Office car No. 25 - now at Ulster & Delaware Historical

Society museum, Arkville, N.Y.

No. 185 at Middletown coal dock

No. 27

No. 249 at Midldletown, 1938

Locomotive 228 at Weekhawken

Locomotive No. 310 fresh from the shops

Locomotive 255 at Middletown

_______

Remembering the ‘Wabash Flyer’

By Richard F. Palmer

For decades the so-called Wabash Flyer was the New York, Ontario & Western’s answer to plush long distance travel between New York and Chicago. It was known Trains #5 (westbound)and #6, (eastbound). nicknamed the Wabash Flyer as for years it operated over the Wabash or Michigan Central railroads between Niagara Falls and Chicago. It was both a first class train with Pullman car accommodations as well as an emigrant train. The original routing was over the New York, Ontario & Western mainline to Oswego; west on the Rome, Watertown & Ogdensburg to Niagara Falls (Suspension Bridge), and then west over the Wabash. The routings changed in later years. For awhile it ran over the Grand Trunk through Canada.

Train #6 crossing Trew Trestle near Pratt's, N.Y. south of Oneida, about 1907.

Train #5 at same location heading north (west on timetable.)

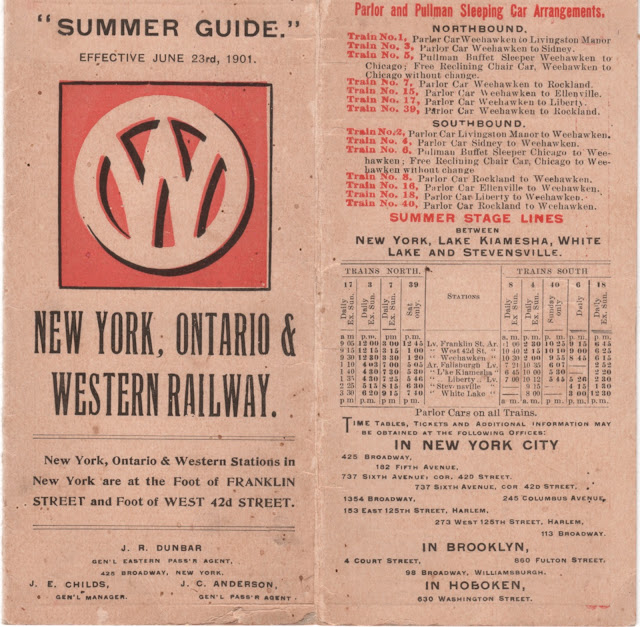

On the N.Y.O & W it officially No. 5, called variously the Chicago Limited or Pacific Express westbound and No. 6, the New York Limit or Atlantic Express eastbound. On the R.W. & O. it was Trains # 110 and #111. It commenced running in May, 1884 out of the newly built Weehawken, N. J. terminal which was a joint venture of the N.Y. O. & W. and the New York, West Shore & Buffalo. For decades thousands of emigrants traveled this route, seeking a new start in the Midwest and West. At various times the train’s official name was the Pacific Express or Chicago Limited westbound and New York Limited eastbound. Although it ran for decades it didn’t financially do as well as the summer trains to the Catskills the N.Y.O.& W. was famous for, due to competition. With the New York Central and Pennsylvania railroads, passengers didn’t have to contend with ferry boat rides in all kinds of weather.

This train was advertised as offering first class passengers Pullman buffet chair and sleeping cars in which meals were served. The fare from New York to Chicago in a berth was $1.50; section, $3 and the premium drawing room, $6. Timetables show the westbound train left New York at 6 p.m. and the eastbound, from Dearborn Station in Chicago, at 3:15 p.m. It was a two-day journey, barring delays. An 1894 timetable shows the train operating over the Grand Trunk from Niagara Falls to Chicago. Annual reports show the N.Y.O. & W. got five percent of the fares for destinations west of Detroit, and 12 percent east of Detroit.

It ran year-round, with primary stops at Cornwall, Campbell Hall, Middletown, Liberty, Cadosia, Walton, Sidney, Norwich, Oneida, Fulton and Oswego. In 1891 the R.W. & O. was leased to the New York Central & Hudson River. Occasionally this train ran in several sections depending on the volume of traffic. The normal scheduled running time was four hours and 20 minutes over this line in 1900, or about 35 miles per hour. Particularly during harvest time the “flyer” might be shunted off onto a siding while long freight trains of cars loaded with apples took priority. This route was very direct but was susceptible to harsh weather, especially during the winter. On more than one occasion the train was nine hours late arriving in Oswego from the west. Coaches were filled with emigrants from throughout Europe. At the N.Y.O. & W. station on West Third Street the westbound train was turned over to the R.W. & O. Jay Knox, a columnist for the Oswego Palladium-Times, wrote:

“ The Wabash Flyer would lay over for three or four hours, while it was being shifted to the R.W. & O. tracks, and would leave over the Hojack the next morning around 4 o'clock and often later. The train was always greeted by large groups of people. Those emigrants were a happy lot and many of them would be bound for states as far west as Idaho, Nevada and California. Most of them were Germans; and a majority of them were seeking homes in Detroit, Chicago and Minneapolis - and other cities.

“They used to leave quite a little money with the eating house near the station. After a period of years the Wabash Flyer was re-routed and became almost forgotten as far as Oswegonians were concerned. Well do we recall the time when we stayed up all night in order to take the train at 4 o’clock, only to learn that it was three hours late. And probably that is where we got our reputation for being ‘night hawks.’” It then proceeded across the river to make a stop at the New York Central station.

This was considered a bad luck train. Three passengers were killed and 20 injured in a head-on collision between Train No. 5 with a switch engine at Parker, a small station near Guilford, Chenango County, on June 19, 1910. The Middletown Times-Press reported on June 20:

“A passenger train laden with emigrants going to the West, running as the second section of No. 5, the Chicago Limited, on the Ontario and Western Railroad, was wrecked at Parker, sixteen miles southeast of Norwich at 2:15 a.m., today.

Three passengers were killed and twenty-five were injured. The wreck occurred when the emigrant train crashed into a locomotive running light.

“The more seriously injured are Percy Furnier, fireman of the locomotive, ankle crushed; B. F.Kingman, engineer of the locomotive, leg broken.

“The engine running light was returning to Sidney from Guilford Summit. Kingman had orders to wait at the summit until the second section of No. 5 had passed, but was dropping back to Sidney when at a sharp curve he ran into the heavily laden passenger train.

“The train was made up of eight coaches and an engine and carried 371 emigrants. It was running about thirty miles an hour, up the heavy grade, and the light engine, making about twenty-five miles, struck it head on.

“When the collision occurred the first passenger coach, an old one, immediately behind the engine, was crushed to pieces, the tender of the engine passing nearly half way through it. All the injured excluding the fireman and engineer of the light locomotive, were in this car, as the other seven coaches of the train remained on the track.”

On September 12, 1912 the train was running at more than 50 miles per hour on the west Hojack when it ran through an open switch at Morton, 30 miles west of Rochester. The engine crashed into a warehouse. Five coaches overturned although the Pullman car stayed upright. There were no serious injuries but the engine and cars were badly smashed.

The Wabash Flyer was also inevitably delayed by weather conditions. At 9 p.m. on February 10, 1912, when it should have already arrived in Weehawken was stalled more than 350 miles away by rail in a 20-foot snow drift at Red Creek. The passengers were fed by local farmers while the train waited to be dug out. It was reported that never in the history of this region had there raged such a continuous snow storm. It started on December 27th and continued every day but one, a total of 43 days. Eight-one inches of snow had there was no sign of it letting up. Through nearly seven feet of snow a small army of shovelers were digging a passageway for trains until the rotary plow could get there. A 40 mile an hour wind packed the cuts.

Wilfred Kearns, son of Ontario Division superintendent Samuel Kearns, said:

“I remember the immigrant train well. It passed through westbound daily around noon carrying almost entirely, immigrants bound for the Middle and Far West. It was known as ‘The Wabash Flyer’ because it ended its run over the tracks of the Wabash Railroad. Its came into Oswego over the New York, Ontario & Western Railroad from Weehawken, N.J., where the immigrants got off the boats.

“There were two railroad stations in Oswego. One was on the east side of the river, which was actually the O.& W. terminal on New York Central tracks. The station on the west side of the river was in the old Lakeshore Hotel. When that burned a new station was built at the same site. The division offices were in another building across the street from the station.

“As a boy of 12, I was down at the station quite often, since railroading seemed to be in my blood. A few doors along Utica street from the railroad offices, a Miss Sullivan had a small candy, tobacco, and grocery store patronized principally by the railroad men. One day as the Wabash Flyer, packed to capacity, was standing at the station, Miss Sullivan suggested that I take some bread and bananas and other comestibles and hawk them along the side of the train. It was very hot weather and the windows were all open. This I did with great success, until a day or so later when my father looked out his office window, saw me, and promptly sent someone to bring me into the office, thus ending my efforts to emulate the Union News Co.”

This train ceased running to Oswego on December 29, 1912 and was rerouted. It was shifted over to the New York Central’s Chenango branch, running between Earlville and Syracuse; west to Suspension Bridge where it was turned over to the Wabash or Michigan Central. It was said this was largely due to the age-old delays encountered on the Hojack line. This continued until June 24, 1917 when the train began running directly to Utica, where it was turned over to the New York Central mainline. It was discontinued on January 28, 1918.

But this wasn’t the end. Following World War I it was restored. An N.Y.O. & W. timetable dated January 1, 1923 shows the Chicago Express operating over the Utica Division to Utica, west on the New York Central; then over the Michigan Central to Chicago via St. Thomas and Windsor, Ontario and Detroit. On February 19, 1928 the train was discontinued.

Wabash Flyer Wreck at Crockett's in 1910

Early in the morning of October 17, 1910 the Wabash Flyer, consisting of the locomotive, baggage car, two sleepers and seven coaches was traveling along at about 35 miles per hour when, a mile west of Crocketts on the R.W.& O. Division of the New York Central when an engine tire slipped off one of the rear driving wheels of the locomotive. It was hurled down a 15-foot embankment, landing on its side, with the tender on top of it. The engineer and fireman jumped off, but the engineer badly sprained an ankle. Nearly 400 feet of track was torn up. The baggage car was hurled down the other side of the bank, landing upside down. The smoking car, filled with passengers, followed the baggage car down the bank. The coaches were left on the rails. There were no serious injuries. Sterling Town Historian

|