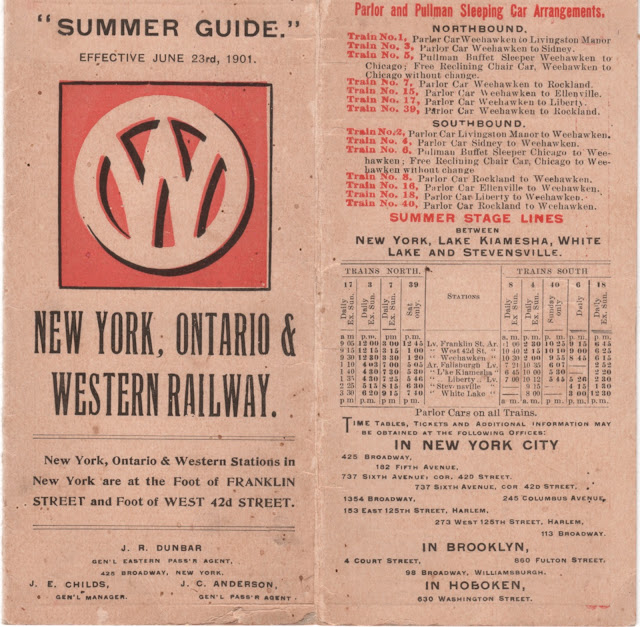

Sketch based on specifications and bill of materials.

South side view New York Central station in 1869.

It has been occasionally asked, “where was the first railroad station in Syracuse?” Since this topic has been barely touched upon in the past, it seems appropriate to discuss the topic in some detail.The first railroad station located within the current city limits was where the Auburn & Syracuse Railroad temporarily ended at West Genesee street. It appears to have been built in late 1837 or early 1838 when horsepower was still used to draw trains.

What slowed things down was the necessity of building a wooden trestle across a large pond that provided waterpower to the Red Mill. This pond covered much of the area just west of what is today South Franklin street which obstructed direct entry into downtown Syracuse. It covered most of what is now Armory Square and provided waterpower for the old Red Mill then located on West Genesee street. The trestle was built on pilings.

On September 3, 1838, Levi Lewis, agent for the Auburn & Syracuse Railroad Company, applied to the village trustees for the privilege of erecting a depot for the use of the company on West Washington street between Salina and Clinton streets. The application was granted, stipulating it was to be no more than 18 feet wide and did not obstruct street traffic. This lasted from September, 1838 to June, 1839 when the first permanent station was built jointly by the Syracuse & Utica and Auburn & Syracuse railroads. By then the A&S had replaced horses with locomotives. It was then removed.

Meanwhile, on July 19, 1838 the Syracuse & Utica applied for permission to build a “car house” on Washington street between Salina and Warren. The application was subject to a public meeting on December 26 at which railroad president John Wilkinson appeared. Village President .W. Leavenworth drafted the resolution granting the Syracuse & Utica Railroad Co. the privilege of building the station. The stipulations set forth in the resolution were that the building would be 49 feet wide. The company would purchase a strip of land four feet wide on the south line of block 101, and one of 26 feet in width on the north line of block 108. The company was instructed to leave an alley 14 feet wide on the north side of the building and a street 33 feet wide on the south side, and to flag the sidewalk on this street to keep the alley in good order.

The railroad company was also required to set out shade trees on both sides of Washington street eastward to Beach street within a year; and to construct a sewer line from the bed of Yellow Brook to Onondaga creek. The company agreed to the conditions and the alley and street so named were subsequently declared a public highway. The center of Washington street was franchised as a right of way for the railroad which lasted until 1936.

The original contract between Daniel Elliott, a local architect and builder, and the Syracuse and Utica Railroad, is dated January 21, 1839. It reveals enough details from which a model could easily be built as it includes specific dimensions and specifications and the bill of materials. The cost agreed upon was $10,400, not including painting; an alternate deducted $350 in case the ceiling joists were omitted. The Engineer had authority to approve or reject materials and workmanship, design moldings and other features not shown on the plans, and to arbitrate disputes between the contracting parties. He certified delivery of materials and work progress, on the basis of which payments were made, 10 percent being reserved until final completion.

The building was 300 feet long and 49 feet wide. Two tracks ran through it lengthwise, passing through double doors 9 1/2 feet wide and 15 feet high. Doors were opened and closed as required. Along the north side of the interior extended a plank platform 12 feet wide. It was reached through six doors along the side and one at each end. The remainder of the floor was paved with brick, set in sand. There is no indication of partitioning or interior finish except covering walls and ceiling with "the best quality of well seasoned pine stuff one inch thick worked to a uniform width and not over 8 inches wide."

The plan seems to have been consistent with early railroad practice - it essentially was just a fancy train shed. One track, adjoining the platform, served for passenger access; the other track could be used for servicing and storing cars and trains. the 12 foot space at the south side could be used for service circulation storage, etc.; doors of the building could be locked. There is no mention of subdividing the space.

The exterior design conformed to the then prevailing Greek Revival style. At each end the facade had five pilasters two feet wide and 20 feet high, with Doric entablature and pediment. Two center bays contained the train doors, and two outer bays contained doors five feet wide and nine feet high, with pilasters inside and outside. Near each end a cupola 8 1/2 feet square projected 16 feet above the roof; presumably they served as ventilators. In addition, six ventilators wee placed in the roof on the north side, evenly spaced. The north wall contained 18 windows, and the south, 12; each had lights 11 by 14 inches, and they were double-hung.

On the outside each was provided with a small cornice, matching over the small doors. Ten center bays on the south side were treated with pilasters 20 feet high, the openings between them filled with "tastefully arranged lattice work," with diamond-shaped openings four feet wide. This was made of 3 by 4-inch pine pieces "halved together and secured by a substantial wood screw at each intersection." On the end facades, the space above the doors was also filled with lattice.

The frame of the building consisted of 31 bents spaced 10 feet on centers, resting on 8 by 10-inch pine sills, which in turn were supported by a stone foundation two-feet thick. The sills were held down by 1/2" x 2 1/2" iron straps 4 1/2 feet long built into the masonry. Eight by 10-inch pine posts 24 feet high were capped by 6 by 8-inch plates; at a height of 15 feet were horizontal girts 8 by 10 inches. Hemlock braces extended from posts to girt and plate, and 3 by 8-inch hemlock studs spaced two feet on centers filled out the wall, to which was nailed 1/2 by 6" pine siding. Pine tie beams squared at 10 by 12-inches and 50 feet long spanned the width of the building.

Braces 16 1/2 feet long extended from posts to the tie beams. Principal rafters of 7 by 9-inch pine were 27 1/2 feet long. They carried an 8 by 8-inch purlin on each slope, which in turn carried upper rafters 4 by 7-inches, spaced on three-foot centers. Braces between principal rafters and purlins helped to stiffen the roof frame. The roof was boarded with hemlock "edge to edge" and covered with "best 1/2-inch shaved shingles Ithaca made" laid five inches to the weather.

The form of truss shown on the drawings does not appear very efficient by modern building standards. It was known by the beginning of the 19th century, for comparable spans, but in this case does not appear to be the usual kind. However, it is the only combination that seems to work out according to the number of length of members specified in the bill of materials. For each truss there is one tie beam 50 feet long, two principal rafters 27 1/2 feet long and two timber struts 16 feet long. There is one 1/1/2-inch diameter iron suspension bolt 14 feet long, two eight-foot long and two, two-feet long - the last obviously to secure the angles. However the truss was made, it stood for 30 years.

Part of the agreement describes the track structure. Two parallel trenches were dug, six inches deep, and sills bedded in them "by heavy repeated blows of a mall." Ties five feet on centers were then laid across the sills and spiked to them. Ties to bear the rails were next placed longitudinally and wooden rails placed above them. At each stage, members were carefully leveled and joints between the members broken. Iron rails, presumably strap rails, finished the operation. They were placed exactly 4' 8 -3/4" apart, measuring from the inside. A tolerance of an eighth of an inch was allowed in centering the wooden and metal components of the rails.