A One-Man Fantrip

By Henry P. Eighmey

(Railroad Magazine, July, 1942)

Ever since wartime restrictions set the block against fantrips on Class I railroads, I have been wondering where we hobbyists could find an outlet for our enthusiasm. One solution to my problem was the Unadilla Valley Railway, a standard-gauge pike which carries freight between New Berlin and Bridgewater in upper New York State. Living at Kingston, N.Y., not far from the twenty-mile line, I was naturally curious to learn about it. Accordingly, I got in touch with E.H. Cook, the Superintendent of Motive Power, and obtained his permission to ride an engine cab.

A two-story frame structure houses the Unadilla’s business office. Behind it are a four-stall engine-house, a freight depot and several smaller buildings, as well as the sidings which make up the yard. At the engine-house I came across No. 1, an old American type, on a track leading to the main line. Smoke was rising lazily from her high stack. However, she was not going anywhere at that time. She was just being kept steamed up for use in case of failure of other motive power. In the winter, though, as I learned later, the little 4-4-0 does active duty in bucking snow.

Then I saw No. 4, a 2-6-2 type, receiving a complete overhauling; and No. 5, another Prairie type, with steam up, probably ready to haul a train. The fourth stall was empty, as the Unadilla has but three engines. On a siding outside the engine-house stood the company’s only rolling stock - two four-wheeled cabooses, a snowplow, several work cars, and a number of weather-beaten, open-end coaches relics of the passenger service which the Unadilla Valley boasted in happier days. I queried an engineer wiper in the roundhouse as to the schedule.

“We haven’t had a time card since we quit hauling passengers ten years back,” he replied. “However, we make two round trips a day, one in early morning, the other in late afternoon.”

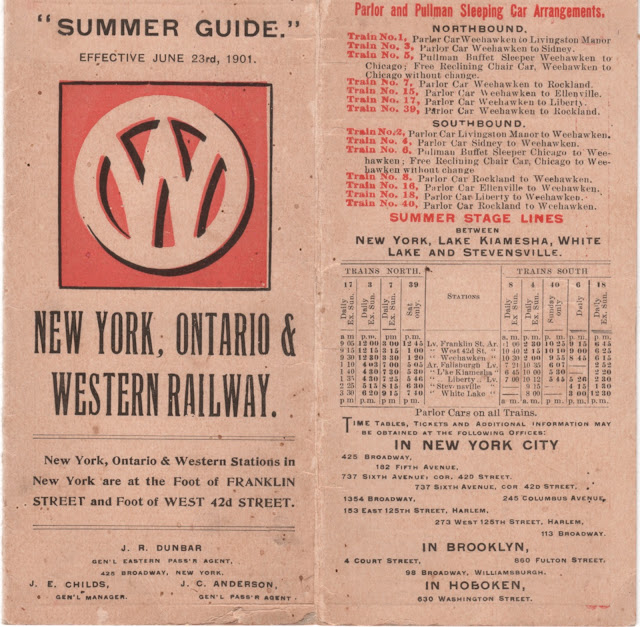

I elected to ride the cab in the later run, and was told to be on hand about four o’clock the next day. When I arrived, No. 5 had been moved out into the yard, ready for the run. George Moore, the fireman, confided that we would start for Bridgewater, the other end of the line, as soon as a New York, Ontario & Western train pulled in with two milk cars.

Engineer Fred Clark beckoned to me to climb into the cab. We eased out onto the train, coupled on one of the old cabooses, and backed down toward a creamery which adjoins the yard. He we kicked the caboose into a siding while we picked up several empties. Then we backed down to the NYO&W for the milk cars. At length we highballed out of the New Berlin yard with ten cars and the caboose on our tail. This is about the average size train on the UV. Four years ago, the fireman disclosed, they chalked up a record by running a drag of 21 cars, nowadays the total seldom exceeds a dozen.

Engineer Clark decided we’d have to roll her if we wanted to connect with the usual Lackawanna train at the terminus. Gathering speed, we passed the last of the sun-bleached passenger cars beside the track and clotted over the switches on the wye which was used for turning locomotives at New Berlin. The freight cars were now banging along behind the little 2-6-2, and I was bumping up and down in the firemen’s seat to the sway of the low-wheeled locomotive. During the few brief spells when my equilibrium was my own was my own I managed to look out the cab window. Although the right-of-way was somewhat overgrown with weeds, I noticed that the lightweight rails were in pretty fair shape, with occasional evidences of recent tie replacements and even a few new concrete culverts.

The engineer and fireman vied with each other in giving me statistics of the road. Over 10,000 tons of anthracite and almost a thousand tons of livestock move over the Unadilla in a year’s time, they explained. The line also handles several hundred cars of milk, 400 loads of cheese from the Kraft-Phenix factory at South Edmeston, and many carloads of miscellaneous commodities. The volume of freight enables the UV to give employment to 35 people and pay the New Berlin tax collector close to $1,500 annually.

Our first stop was South Edmeston, about five miles out, where three of the Unadilla’s customers are located - a feed and grain dealer, the cheese works and a big chicken farm. The brakeman deftly cut in two cars from the cheese plant, but neglected to set out two loads we had for the same company.

“We’re in too much of a hurry,” Fred Clark explained. “We’ll drop them off on the return trip.”

Six miles further on, at West Edmeston, we halted to fill the tank with water and pick up an empty boxcar. We whizzed past the next station, River Forks, and arrived at Bridgewater in time for the meet with the Lackawanna freight. Here we cut the engine loose, backed her down a siding until the caboose was on the pilot of No. 5, and pushed the train onto the DL&W tracks. The engine was then turned around on a wye, and the brakemen coupled her onto the nine cars which the Lackawanna had brought for the UV.

As we steamed out of Bridgewater a bright moon was shedding romance on the shadowy trees and gleaming stream of the Unadilla Valley. We dropped a boxcar and a gondola of coal at Leonardsville, then proceeded to South Edmeston to deliver the two cars which had made a round trip. It was about 8 p.m. when the forms of the old passenger cars poking out from the brush along the right-of-way in New Berlin informed me that the trip was almost over.

The train crew then did their last duties of the night, shoving the cars on a siding, and turned the locomotive on the wye and placed in charge of the engine-house mechanic. The men lost no time in setting off early for their homes, but I lingered awhile in the vicinity of the yards, meditating on the thrills I had enjoyed in my one-man mantrap over the Unadilla Valley Railway.